Phantoms in the Family: Chester Novell Turner’s Tales from the QuadeaD Zone

Art & Trash, episode 6

Phantoms in the Family: Chester Novell Turner’s Tales from the QuadeaD Zone

Stephen Broomer, March 11, 2021

The films of Chester Novell Turner reflect a deep understanding of grief and tragedy in the American family, all while mirroring the ironic story structures of The Twilight Zone and Tales from the Crypt. Turner’s movies were capable of being both exploitative and compassionate, fiercely intelligent in their satire, yet at times gleefully dumb, without apology. This episode deals with Turner's second and, to date, final work, an anthology horror film in which each of his three stories featuring tortured, toxic, and tragic families. Stephen Broomer discusses Turner's approach in relation to horror fandom that inspired him, the running themes of forgiveness and betrayal, and the personalizing traits of Turner's storytelling.

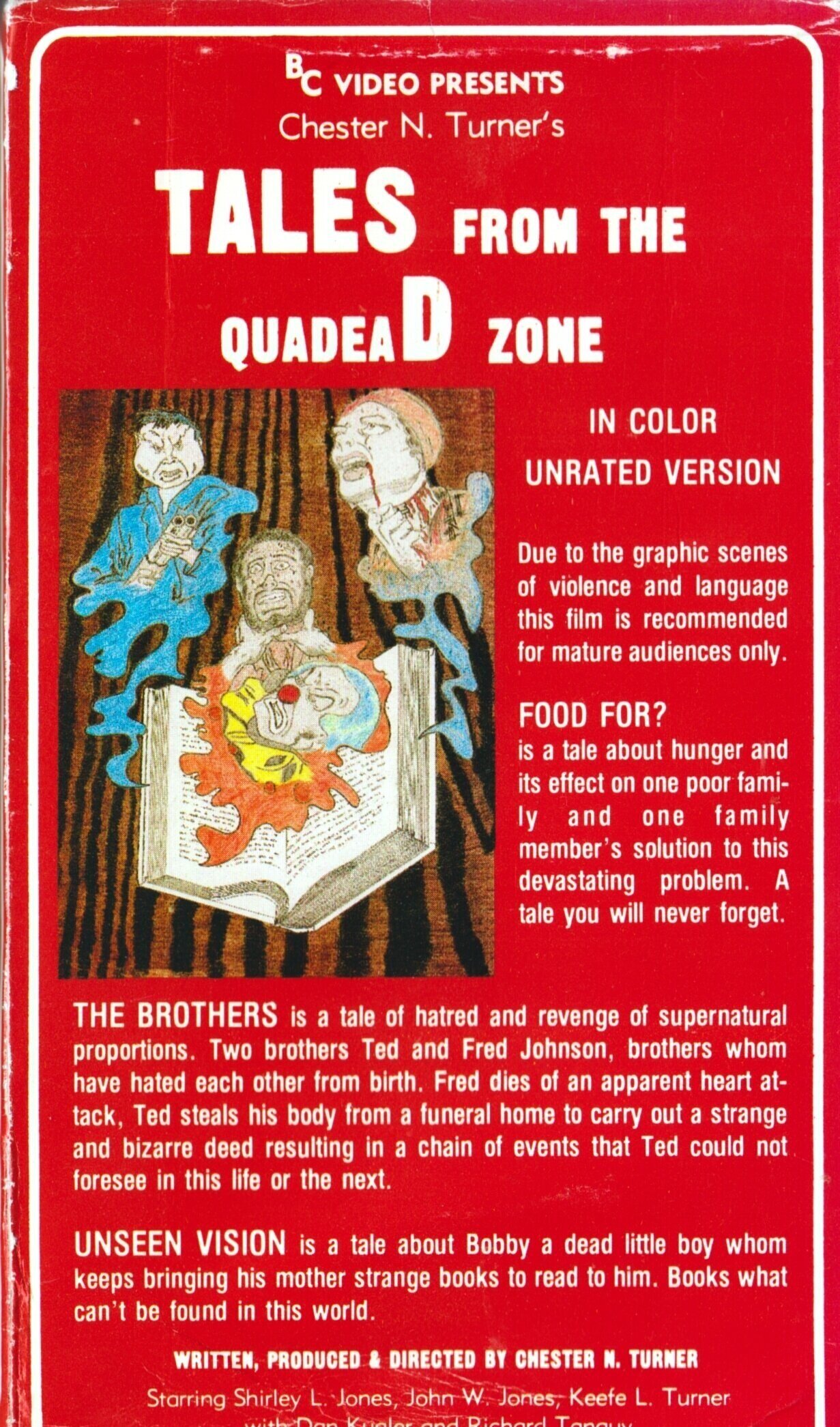

Tales from the QuadeaD Zone was originally published by Turner himself on VHS, following bad experiences he had with commercial distributors. It was re-released as a limited edition DVD, paired with Black Devil Doll from Hell, from Massacre Video on November 12, 2013, an edition that is now out of print..

“Whether Turner is defying rules he never learned makes no difference; the ultimate effect is a more personal cinema, and after all, there are no rules in the game of fright.”

SCRIPT:

The films of Chester Novell Turner reflect a deep understanding of grief and tragedy in the American family, all while mirroring the ironic story structures of The Twilight Zone, and Tales from the Crypt. Turner belongs to an informal cohort of American amateur filmmakers who emerged from the home video rental market of the early 1980s. With the advent of home video, the tools for making and distributing videotapes became affordable and potentially profitable for aspiring genre and exploitation filmmakers. While those filmmakers were commonly inspired by the professional execution of Hollywood movies and the independent, commercial cinema of the grindhouse, they often distinguished themselves by their passion, by the strangeness of their methods, and the occasionally subconscious pathology of their stories. Like earlier generations of amateur filmmakers, these video shooters could serve as founts of uncommon insight, bending the rhetorical discourse of cinema. They would tell stories that aspired to the same ends as mainstream commercial movies, but that played out on an inevitably personal scale. Turner’s movies were capable of being both exploitative and compassionate, fiercely intelligent in their satire, yet at times gleefully dumb, without apology.

Turner made two feature films, both in collaboration with his partner at the time, Shirley Latanya Jones, and a cast and crew of their friends and family. Turner had learned to make films by taking correspondence courses, following a lifelong interest in the sequential storytelling of comic books, and an enthusiasm for Universal monster movies of the 1930s. His films were self-assured satires, made with joy by small crews of friends and family. The first, Black Devil Doll from Hell, is an erotic horror movie that takes inspiration from Dead of Night and anticipates Child’s Play, with Turner’s brother Keefe voicing a lustful, evil, sentient doll designed, according to Turner, as a cross between a farmer and Rick James. Black Devil Doll from Hell had been developed as an episode of an anthology horror film, but it had taken on its own separate life; the rest of that intended anthology-horror film became Turner’s second feature, Tales from the QuadeaD Zone. The title is a tribute to the Twilight Zone, with the mysterious portmanteau quadead – likely an allusion to Quadruplex tape, commonplace 2” videotape used for broadcasting. This interpretation fits Turner’s circumstances, that these are stories that are made possible through the illusions of videotape. The ambiguity of this title is in keeping with the mischief of much of the film itself: “there are no rules in the game of fright.” So the filmmaker’s brother Keefe declares in the film’s rapped introduction.

Tales from the QuadeaD Zone is not merely an anthology of horror stories, but a thematic anthology, with each of its three stories featuring tortured, toxic, and tragic families. The film itself is dedicated to Turner’s father, and is very much a family affair, with members of both the Turner and Jones families featuring prominently; in other words, this is a film about familial suffering, discord and pain made by a man who has a strong, firsthand understanding of the love and sacrifice of family. Shirley Latanya Jones, who also made the film’s opening illustrations, plays a suburban mother, who here acts a kind of cryptkeeper, as the mother is prompted by her son Bobby’s unseen ghost to tell him stories. Bobby makes his presence known through a persistent, incomprehensible whisper, through a wind that blows through the mother’s hair, and through floating cups and chairs that move on their own.

The mother entertains Bobby’s ghost by reading him stories from a Bible that has been decorated with a hand-drawn cover bearing the film’s title. The first story, “Food For ?”, is a darkly comic variation on the Ballad of Hollis Brown. The Novac family are introduced by Jones as poor crackers. The father’s grace is a rhyming couplet offered more in complaint than gratitude, telling that they’re poor, with eight at the table and food for four; and later, that the food will keep them alive but there’s only food for five. His prayers are followed by violence, as his children kill each other off through brute competition to get their share. This eventually leads to a massacre led by one of their sons, armed with a rifle. At the end of the segment, Turner shows the faces of the family members with texts telling their fates: died of a rifle shot to the face, died of a rifle shot to the chest. The images of the mother and father are accompanied by strange, ironic fates: “living high on the hog in the witness protection program.” The mother and father, who had made gruesome sport of their desperation, face no punishment at all. On the contrary, they alone survive and prosper.

“In ‘Food For,’ the protagonists, with their prayers, avoided personal responsibility for their lot. ‘The Brothers’ is concerned instead with forgiveness and respecting the dead.”

The second story, The Brothers, features Ted and Fred, brothers whose mutual antagonism continues beyond the grave. Ted steals Fred’s corpse from a funeral home; this prolonged sequence benefits from qualities particular to home video recording - the light trails of the corpse thieves’ flashlights and the relative darkness of these scenes suggest that it is being shot for the most part in available light, a common limitation of amateur video. The dialogue, much of it slightly muted and inaudible, furthers this effect of an observational style. Ted plans to bury Fred in his basement after dressing him up as a clown. Ted’s hysterical, forced laughter is stretched over unusually long takes. As that familiar casio vamp creeps in on the soundtrack, Fred’s ghost regains possession of his body. On the soundtrack, the corpse bellows in an unearthly medley of cartoon duck quacks and terrifying, heavily reverberated, almost incomprehensible speech. Finally, Ted is killed with a pitchfork. He convulses and curses Fred, who laughs and exits. In Food For, the protagonists, with their prayers, avoided personal responsibility for their lot. The Brothers is concerned instead with forgiveness and respecting the dead. Ted’s inability to forgive his brother, and his transgression against the dead, are provocations that meet a just reward. In a cruel irony reminiscent of EC Comics, Ted had been digging his own grave, a literal manifestation of a governing theme.

“Turner’s editing, which integrates stylized shots and inserts, feels more like evidence than art.”

In the final story, Unseen Vision, the framing device itself is the setting of another tale of family dysfunction and betrayal. Daryl, Bobby’s grieving father, interrupts the mother’s storytelling and interrogates her about the storybook. He then beats her with the book. The ensuing struggle is brutally realistic, the impact of his strikes emphasized by the rawness of the home video aesthetic. This makes Turner’s editing, which integrates stylized shots and inserts, feel more like evidence than art. After this prolonged beating, the mother skewers Daryl with a blade, and leads him in a “final dance” as he bleeds out onto the floor. The mother’s howls of anguish, like Ted’s prolonged laughter, have an arresting authenticity about them. Daryl manages to call the police, and they arrive to find the mother caked in blood. She goes to the bathroom, finds a razor blade and contemplates suicide, to the cheerful sounds of a casio tune. Her reverie is intercut with scenes of happier days spent with Bobby at a playground. When this is over, she cuts her own throat. Her suicide reunites mother and son, as chromatic / chromakey phantoms who sit together in their former home. As the film ends, she begins to tell him a final story: their own story, about how much they loved each other.

The narrative content of Tales from the QuadeaD Zone is quite spare, as is the dialogue, which is often overwhelmed in the mix by Turner’s striking casio score; the film defies the claim made by Alfred Hitchcock that drama is life with the dull bits cut out; it is a film in which no less than three violent acts of family murder occur, and yet, much of its time is spent in moments of waiting or in awkward anticipation, as with Ted’s hysterical laughter, the mother’s prolonged cries of anguish, and the casual chatter of the Novac dining table. While these actions pad the running length, they also amplify our anticipation in a way that is entirely different from the self-conscious strategies of mainstream cinema that develop tension through intercutting, through rhythm and restraint, through suggestive framing. Turner had desired to emulate the Universal monster movies, the Twilight Zone, the EC Comics in which, as in cinema, beats of time are measured in frames. His sources had emerged out of a long lineage of continuity, where action is condensed and developed, where storytelling is both visual and punctual. These are the roots of his passion, but Turner veers from this tradition, out of, we might speculate, a love for his characters and the scenes that he’s creating. The consequence is a total and welcome de-professionalization of the film, marking it with a greater intimacy, furthering this observational style that seems to haunt the film’s quietest moments. It allows these performers, even at their most histrionic, to occupy these characters more fully. It defies traditional storybeats to make room for spontaneity, or even, simply, space. Whether Turner is defying rules he never learned makes no difference; the ultimate effect is a more personal cinema, and after all, there are no rules in the game of fright.

The climax is especially chilling in its portrayal of the carnage and impact of domestic violence. The film’s themes are made most lucid in the conclusion, in the bittersweet reunion of mother and son; it’s implied that, like the other characters, they are trapped. Ted, unshakeable in his bitterness, is trapped in the fate he had laid out for his own brother’s body; the Novacs, mother and father, survive “high on the hog” in witness protection, well-fed and with no more mouths left to blame for their lot; and the mother and Bobby are trapped happily in their love, in a cycle of endless storytime. Tales from the QuadeaD Zone is about the erosion of love in families; these families collapse because of desperation, inadequacy, jealousy. The only people who are spared this are Bobby and his mother, victims rather than perpetrators of family violence. They are also ear-witnesses to these other tales. And even if there are no formal rules in the game of fright, this outcome cuts to the bone more deeply than that of the average horror movie. With Tales from the QuadeaD Zone, Chester Novell Turner offers a message of compassion, forgiveness, and the sanctuary of a mother’s love, blanketed within a shell of gore, pain and heartbreak.